To design a register machine, we must design its data paths (registers and operations) and the controller that sequences these operations. To illustrate the design of a simple register machine, let us examine Euclid's Algorithm, which is used to compute the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers. As we saw in section 1.2.5, Euclid's Algorithm can be carried out by an iterative process, as specified by the following procedure: function:

| Original | JavaScript |

| (define (gcd a b) (if (= b 0) a (gcd b (remainder a b)))) | function gcd(a, b) { return b === 0 ? a : gcd(b, a % b); } |

A machine to carry out this algorithm must keep track of two numbers,

$a$ and $b$, so let us

assume that these numbers are stored in two registers with those names. The

basic operations required are testing whether the contents of register

b is zero and computing the remainder of the

contents of register a divided by the contents

of register b.

The remainder operation is a complex process, but assume for the moment that

we have a primitive device that computes remainders. On each cycle of the

GCD algorithm, the contents of register a must

be replaced by the contents of register b, and

the contents of b must be replaced by the

remainder of the old contents of a divided by

the old contents of b. It would be convenient

if these replacements could be done simultaneously, but in our model of

register machines we will assume that only one register can be assigned a

new value at each step. To accomplish the replacements, our machine will use

a third temporary

register, which we call

t. (First the remainder will be placed in

t, then the contents of

b will be placed in

a, and finally the remainder stored in

t will be placed in

b.)

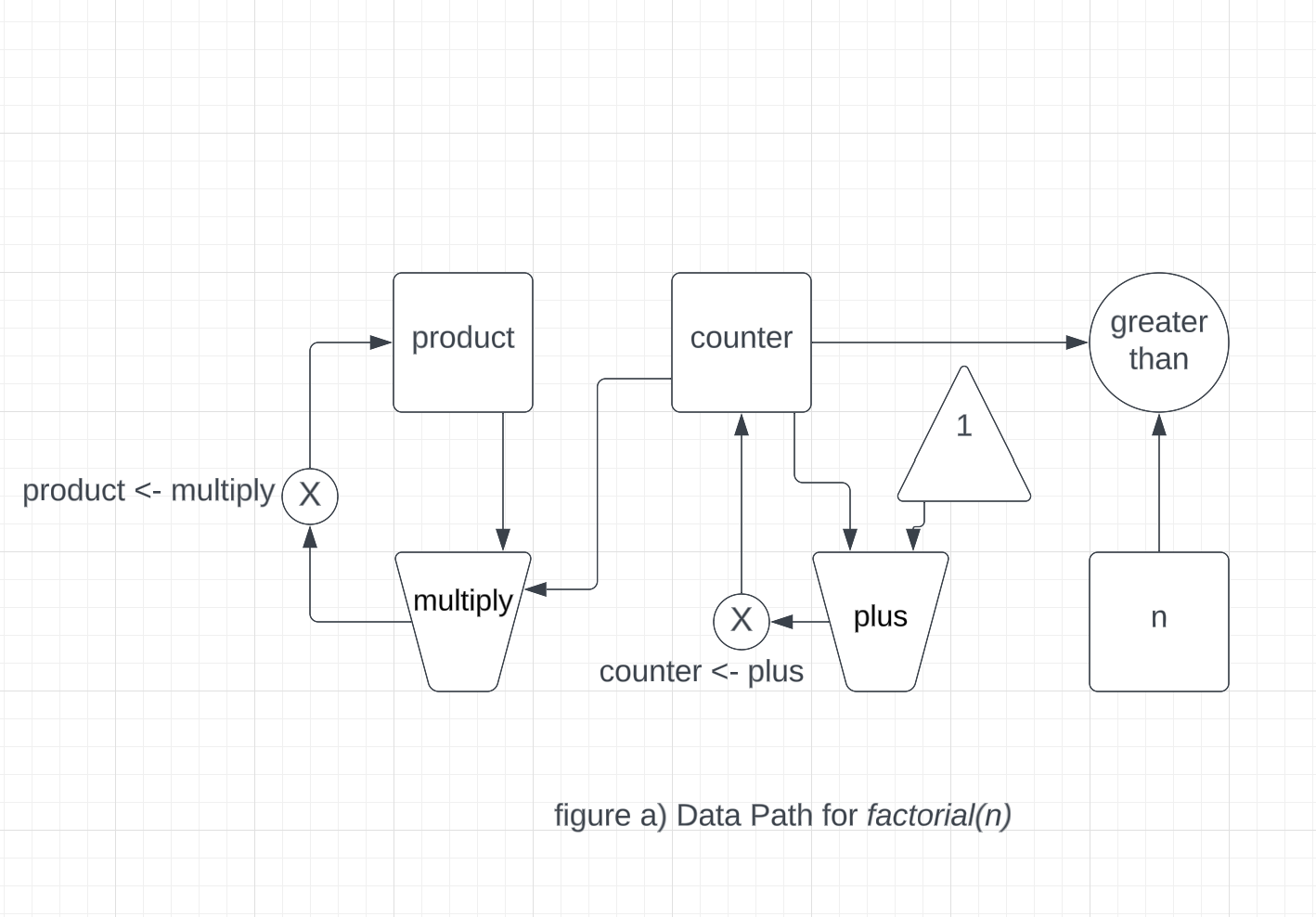

We can illustrate the registers and operations required for this

machine by using the

data-path diagram shown in

figure 5.1. In this

diagram, the registers (a,

b, and t) are

represented by rectangles. Each way to assign a value to a register is

indicated by an arrow with an Xa button—drawn as $\otimes$— behind the

head, pointing from the source of data to the register.

We can think of the X as a button that, when pushed,When pushed, the button allows

the value at the source to flow

into the designated register.

The label next to each button is the name we will use to refer to the

button. The names are arbitrary, and can be chosen to have mnemonic value

(for example, a<-b denotes pushing the

button that assigns the contents of register b

to register a). The source of data for a

register can be another register (as in the

a<-b assignment), an operation result (as in

the t<-r assignment), or a constant

(a built-in value that cannot be changed, represented in a data-path

diagram by a triangle containing the constant).

An operation that computes a value from constants and the contents

of registers is represented in a data-path diagram by a trapezoid

containing a name for the operation. For example, the box marked

rem in

figure 5.1 represents an operation that

computes the remainder of the contents of the registers

a and b to which

it is attached. Arrows (without buttons) point from the input registers and

constants to the box, and arrows connect the operation's output value

to registers. A test is represented by a circle containing a name for the

test. For example, our GCD machine has an operation that tests whether the

contents of register b is zero. A

test also has arrows from its input

registers and constants, but it has no output

arrows; its value is used by the controller rather than by the data

paths. Overall, the data-path diagram shows the registers and

operations that are required for the machine and how they must be

connected. If we view the arrows as wires and the

X$\otimes$ buttons as switches, the data-path diagram

is very like the wiring diagram for a machine that could be constructed

from electrical components.

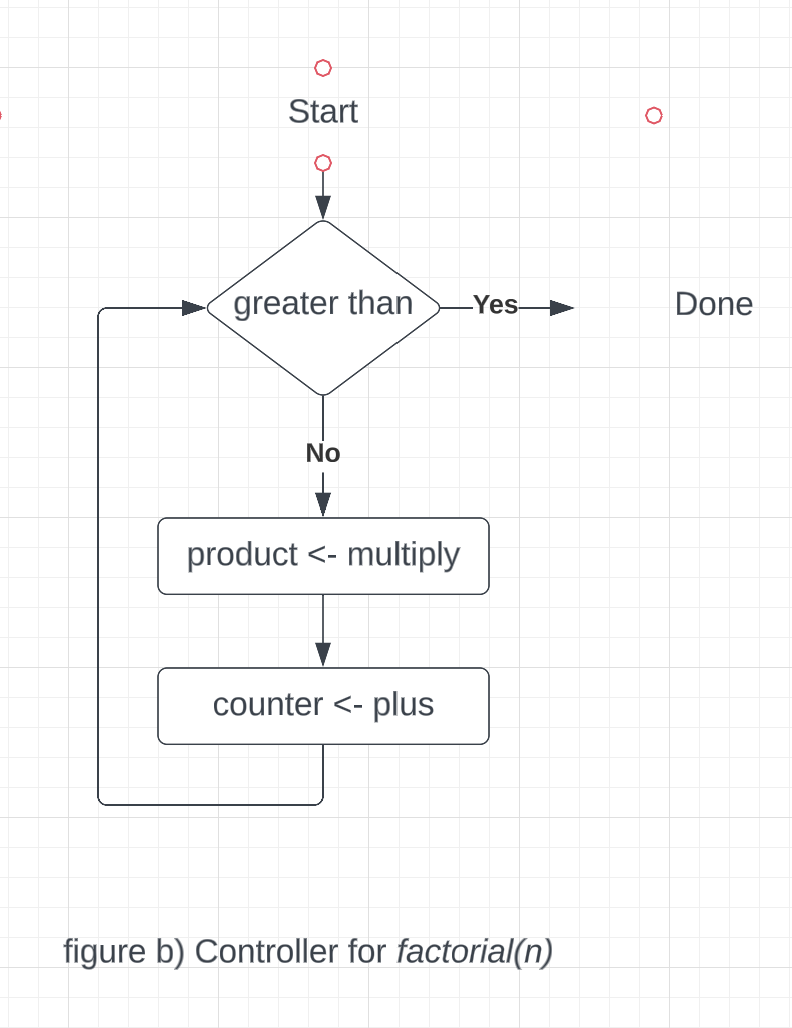

In order for the data paths to actually compute GCDs, the buttons must

be pushed in the correct sequence. We will describe this sequence in

terms of a

controller diagram, as illustrated in

figure 5.2. The elements of the

controller diagram indicate how the data-path components should be operated.

The rectangular boxes in the controller diagram identify data-path buttons

to be pushed, and the arrows describe the sequencing from one step to the

next. The diamond in the diagram represents a decision. One of the two

sequencing arrows will be followed, depending on the value of the data-path

test identified in the diamond. We can interpret the controller in terms

of a physical analogy: Think of the diagram as a maze in which a marble is

rolling. When the marble rolls into a box, it pushes the data-path button

that is named by the box. When the marble rolls into a decision node (such

as the test for

b$\, =0$), it leaves

the node on the path determined by the result of the indicated test.

Taken together, the data paths and the controller completely describe

a machine for computing GCDs. We start the controller (the rolling

marble) at the place marked start, after

placing numbers in registers a and

b. When the controller reaches

done, we will find the value of the GCD in

register a.

| Original | JavaScript |

| (define (factorial n) (define (iter product counter) (if (> counter n) product (iter (* counter product) (+ counter 1)))) (iter 1 1)) | function factorial(n) { function iter(product, counter) { return counter > n ? product : iter(counter * product, counter + 1); } return iter(1, 1); } |